Aug 8, 2025

#architecture

#coding

“I don’t think about programming as a technical thing… I think about it as a way of thinking.”

— Casey Reas

Architecture is not static. It has always evolved with the tools of its time—pen, paper, CAD, BIM, and now, code.

It might sound like a dramatic leap to some, but learning to code as an architect isn’t about becoming a software engineer. It’s about reclaiming agency in a design world increasingly shaped by computation. It’s about expanding what we can imagine, model, and ultimately build. For me, coding became an unexpected but essential extension of my architectural thinking—first through generative experiments, then through interactive tools, and eventually through workshops and artworks that merged space with systems.

Let’s be honest: no one went to architecture school to write lines of syntax. Most of us were drawn in by material, form, atmosphere, storytelling. But somewhere along the way, I realized that the languages used to shape buildings and the languages used to shape algorithms weren’t as different as they seemed. In both, you define rules. You explore outcomes. You iterate. You make decisions. You navigate constraints.

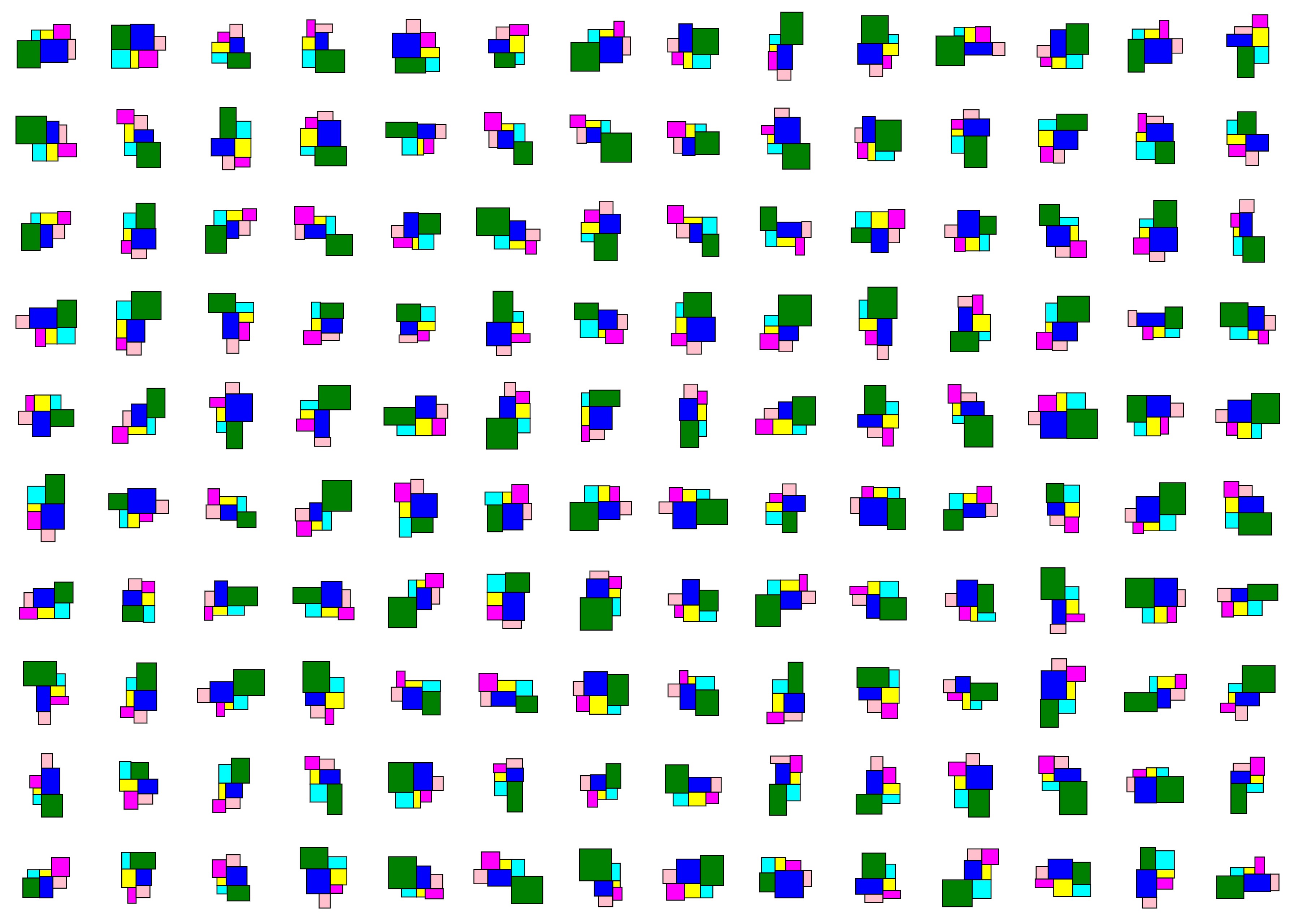

In my early explorations, I was drawn to systems—how one input could ripple through a structure, how form could emerge from a set of relationships rather than a fixed silhouette. Coding gave me a way to materialize that curiosity. It began with simple tools—Processing, p5.js, some Python scripts—but quickly grew into something more generative. I wasn’t just drawing anymore. I was building systems that could draw themselves.

One example that shaped my own understanding of this was the Freeplan project. In that work, I wasn’t trying to “design” the final form. I was designing the logic behind the form. Spatial configuration wasn’t predetermined—it emerged from relationships, behaviors, and constraints. That approach could only take shape through code. It allowed me to test not just formal ideas, but how space itself might behave under certain rules.

This shift completely changed how I thought about design. When you code, you're not locked into a single solution. You're defining behaviors, not just outcomes. Imagine not just drawing a facade, but writing a rule that allows it to adapt to different sun angles, programs, or even emotional moods. Imagine being able to automate the boring stuff—naming layers or exporting tens of renders—but also opening up new forms of expression. That’s what computational design offers: both control and unpredictability.

I’ve seen this in practice. In workshops, students often begin intimidated by code, unsure of how to even type a “for loop.” But within hours, something clicks. They realize that with just a few lines, they can create intricate geometries, simulate natural behaviors, or generate endless variations of a concept. It becomes playful. It becomes empowering.

Of course, the benefits go beyond creativity. Coding improves efficiency. It allows you to build tools that serve your own design logic, rather than adapting your design to someone else's software. Whether it's scripting in Rhino or prototyping with JavaScript, you begin to develop your own workflow language—one that fits your style, your obsessions, your constraints.

And then there’s the collaboration aspect. We increasingly work alongside developers, engineers, data scientists, and roboticists. Speaking even a bit of their language breaks down barriers. It fosters experimentation. It makes new kinds of projects possible—interactive installations, intelligent systems, even AI-driven design workflows. Being able to engage with these different domains doesn't mean abandoning architectural thinking. On the contrary, it creates space to apply it in new, unexpected ways.

And perhaps most importantly, it keeps architecture fun. It reintroduces wonder. When I write a function that unexpectedly creates a beautiful form, it feels like a conversation with the machine. I give it a set of rules; it gives me back surprise. It’s not deterministic—it’s dialogic.

We’re in a moment where the boundaries between architecture, art, design, and technology are visibly blurring. While coding may not be the answer for everyone, it offers architects a way to navigate this overlap with more flexibility and curiosity. It’s not about future-proofing careers or chasing trends, it’s about engaging with a broader ecosystem of tools and ideas that are already shaping the built environment.

And the truth is: it’s more accessible than ever. There’s no need to start big. Just open up a simple environment like Processing or Grasshopper, and start playing. Explore patterns. Build rules. Break them. See what happens. If you’re unsure where to begin, I’ve shared some thoughts and resources in Where Should Architects Start Coding, which might help you take that very first step.

So if you’re an architect wondering whether to take the leap, here’s my take: don’t learn to code because it’s trendy. Learn to code because it sharpens your thinking. Because it gives you freedom. Because it lets you dream with logic, and build with imagination.

That’s what keeps me in it. Not the syntax, but the sensation that something new is always just one function away.